Star Tracker Thermal Boresight Testing

Summer 2023Planet

Overview

Planet is an Earth observation satellite company that provides high-frequency goespatial data. In order for satellites in LEO to take high quality images of the Earth, they must have fine pointing knowledge and control. My project focused on characterizing the uncertainty of the highest precision attitude sensor, the star tracker, specifically relating to its performance under thermal changes.

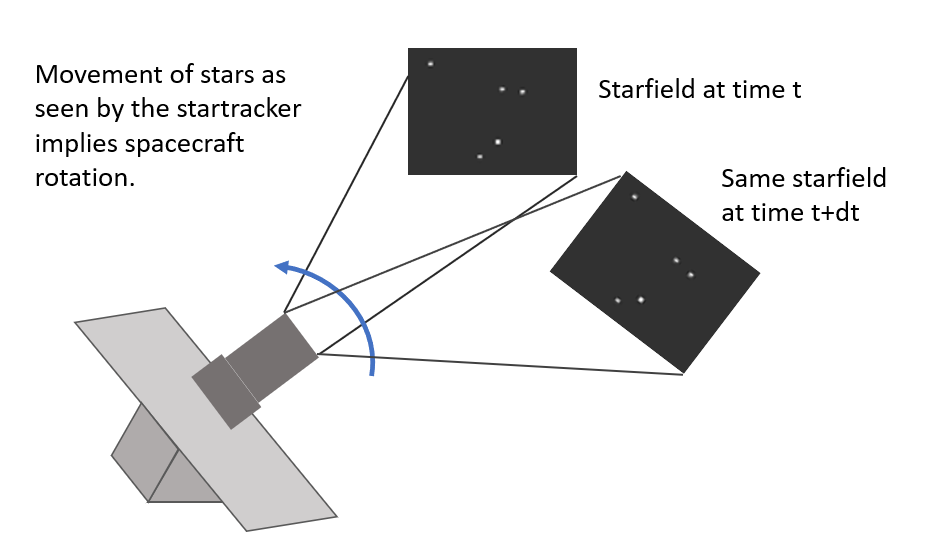

A star tracker is a sensor that estimates spacecraft attitude in inertial space. In its simplest form, it is composed of a camera and a small computer. It works by taking an image of the starfield, determining the locations of the stars in the image, and comparing these to known inertial locations of the stars stored in a catalog on its computer. Any drift of the stars in the camera sensor is interpreted as a change in the spacecraft attitude. Typical star tracker accuracy is on the level of arcseconds (1/3600 of a degree).

Ideally, a star tracker is athermal: the attitude estimate is uncorrelated with the star tracker temperature. However, heat causes materials in the star tracker assembly to expand, which is seen by the star tracker camera sensor as a shift in the starfield. Thus, thermal loads on the star tracker can introduce error into the spacecraft attitude estimate, and this error needs to be characterized in order to understand the uncertainty of the star tracker attitude estimate. My goal was to identify the star tracker components that were deforming the most due to temperature, and to quantify the error in arcseconds per unit temperature.

Contributions

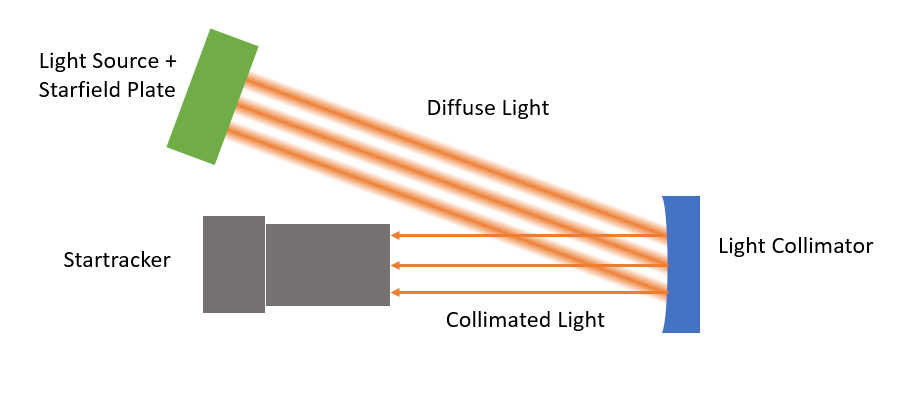

To test the thermal effects on the star tracker attitude estimate, I set up a testbed with a light source and star tracker. Diffuse light would shine through very small holes in a plate, bounce off a light collimator that made the light look like it was from an infinite distance away, and be collected by the star tracker camera. I added resistors and thermocouples to the star tracker housing in order to heat the assembly and measure the temperature of individual components.

A typical test involved heating and then cooling the starcam assembly while recording images. Although the camera and the lightsource were stationary, the locations of the “stars” in the image sensor shifted over the course of the test due to thermal expansion in the star tracker. With this information, I could calculate the change in star locations per degree Celcius.

Because star trackers operate with such high precision, the system was extremely sensitive, and I spent most of my summer debugging and validating the test setup.

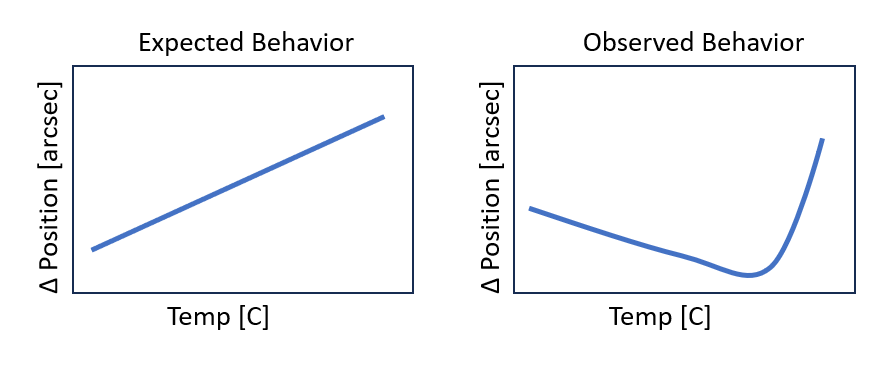

An early problem I encountered was that the star tracker was not initially insulated enough from the test setup. Components in the star tracker should expand linearly with temperature, which would be visible as a linear relationship between the star tracker temperature and the change in position of the stars on the sensor. However the results were showing the stars change directions of motion over the course of heating the starcam. To investigate this behavior, I added more temperature sensors to the sensor and testbed, and I discovered the star tracker and the mounting bracket were not as thermally isolated as my model assumed. The bracket acted as a heat sink for the star tracker, and its subsequent deformation was causing the nonlinear behavior. After adding washers made of G10, a material with low thermal conductivity, to isolate the star tracker from the bracket, the star motion assumed the expected linear relationship.

Eliminating thermal effects caused by the test equipment allowed me to move on to isolating individual startracker components and characterizing their thermal deformation effects. As shown above, the star positions moved in linear, repeatable directions and magnitudes. If I disassembled the star tracker, adjusted one of its components, reassembled the star tracker, and performed thermal testing, I could compare the results with the nominal startracker assembly to understand the effect the component had on the motion. By systematically adjusting the star tracker’s components, I was able to map the star motion to each component. Using this approach, I identified the set of components that most severly affected the star motion.

In addition to characterizing the thermal deformation of the individual startracker components, I also formed an estimate of the error in the star tracker attitude solution due to this deformation. Overall, my work provided a greater understanding of how the star tracker solution is affected by heat and enabled the team to investigate mitigation strategies in order to reduce the error.